Walker Percy and the Existential Quiz

Plus two sample questions for you to complete on your own

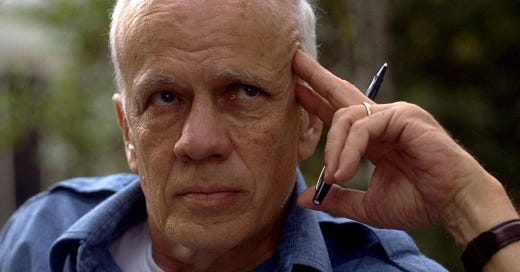

Walker Percy’s Lost in the Cosmos is my favorite book. I’ve read it multiple times, and I think it is his best work. Even Percy thought it contained his most abiding accomplishment. In his 1984 conversation with Jo Gulledge, Percy said,

“The intermezzo in Lost in the Cosmos—a primer on the semiotics of the self—is, despite its offhand tone, as serious as can be. I have never and will never do anything as important. If I am remembered for anything a hundred years from now, it will probably be for that.”

What is Lost in the Cosmos? Well, for one, it is a satire on the self-help genre (indeed, it is subtitled “The Last Self-Help Book”). It is a strange and glorious blending of fiction and non-fiction. The “intermezzo” referenced above is a brief account of how signs differ from symbols. There’s a short vignette of the Phil Donahue show featuring an alien, a Confederate Soldier, and John Calvin. There are at least two space odysseys. And then there are quizzes, oh the quizzes, which are perhaps my favorite part.

Percy mastered the short quiz and made it a vehicle for upsetting his readers’ presuppositions. Indeed, quizzes as such invite reader participation. For this reason, Marshall McLuhan might call the quiz a cool medium, one inviting audience engagement, much like a seminar invites participation as opposed to a lecture. With quizzes, the reader fills in the gaps. In an oddly satisfying way, Percy’s quizzes function a bit like Thomistic articles; they’re filled with objections that appear reasonable, at least on the surface.

Percy will ask questions like: Why didn’t the word boredom exist before the 18th century? Why do people buy coffee tables that don’t look like coffee tables (i.e., why turn a lobster trap or stone slab from an old morgue into a coffee table)? Why do people, especially young people, turn to drugs? And then he’ll give you a list of possible answers without overtly telling you which answer he thinks is the correct one.

The quiz is a very powerful rhetorical device. And the question is the engine of the quiz. Questions disarm while simultaneously directing people’s attention to certain aspects of reality.

Anyway, in imitation of Percy, I offer you the following existential quiz composed of just two questions. If this quiz happens to generate enough interest among readers, I’ll post more.

Existential Quiz: The Statistical and Genetic Self

Question 1: Why do most people fail to recognize the following statement as an ironic fiction: “9 out of 10 people will believe any statistic you tell them”?

Choose the best possible answer below:

A) We are used to hearing statistics, and we tend to give people the benefit of the doubt when they reference statistics. Who has time to look up all the statistics they hear? I certainly don’t. Furthermore, nice people tend to trust others and try to avoid looking for ulterior motives. Who knows? Maybe 9 out of 10 people really do believe any statistic you tell them….

B) Not everyone fails to see the irony in this fake statistic. Emotional, artsy, hipster types tend to be cynical and ironic by nature, and they tend to see through this stupid little joke.

C) We actually don’t know enough about this statement to say whether or not it is an ironic fiction. How large was the sample size? Who conducted the study that led to this statistic? Was the study conducted over a long enough period of time? Also, you should probably define what you mean by “ironic fiction.”

D) While this fake statistic is an ironic fiction, it is actually, somehow, a true statement about the world in which we live. In our current historical moment, that which cannot be measured cannot be said to exist. In our day, numbers have taken on a higher degree of reality than everything else. Indeed, numbers appear more real than the reality they purport to refer to. If something cannot be measured, it’s not real. Hence we find ourselves measuring all sorts of things that actually cannot be measured (e.g., intelligence with things like IQ tests and happiness with things like GDP, etc.). We’re at home in a world of numbers and statistics, and we take numbers and statistics for granted. Hence, we trust numbers and statistics at first glance.

E) None of the above.

Question 2: Why do people send their blood samples to 23andMe?

Choose the best possible answer below:

A) Because it is interesting to see all the various geographic regions and nationalities from which you descend. Ultimately, it is simply curiosity that motivates people to test their DNA. Also, science is beautiful. According to 23andMe.com’s “About Page”: “Science should be fun. It should be easy to understand so everyone (not just the scientifically inclined) can use it and benefit from it in meaningful ways. But science should also be...science. And 23andMe is built on the latest science.” People use 23andMe because they’re curious, and science satisfies our curiosity to know things, especially things about ourselves.

B) People use 23andMe for the same reason they use Ancestry.com, a website that helps you fill out your family tree. The knowledge you get from this site isn’t useful so much as it is informative: it informs you of who you are. Our genes determine everything about us: our eye color, height, the size of our brain, our intelligence, our behavior, our temperament, etc. Thus, it follows that the science of genetics can best inform us as to who we really are.

C) I’m not sure what you’re talking about. I would never use 23andMe. You really think I’m going to give my genetic information over to a publicly traded company? I don’t care what they say about how well they protect the details of my DNA. It ain’t happening. Just imagine a health insurance company declining your request for coverage since your DNA reveals that you have a genetic predisposition for what will eventually become a preexisting condition. No. It’s not for me. I don’t know why people use it. Maybe they’re idiots.

D) Because they want to prove that their parents aren’t actually their real parents. Jerry Springer: “You are not the father.”

E) Because they’re reading about Gregor Mendel and his punnett squares, and there’s nothing more fun than turning your very self into an experiment.

F) People have different reasons for sending their blood samples to 23andMe. Quit trying to be cute.

G) None of the above.

Leave your responses to Questions 1 and 2 in the comments section below with justifications for your answers.

Thanks for reading, whomever you are. If you think others might find it interesting or thought-provoking, why not share it with them? And also, why not leave a comment or a question or a provocation below? You’re allowed to do that, you know. You could even come up with your own quiz question and leave it here for others to take. One last thing worth mentioning: Whereas Lost in the Cosmos is a most excellent book, it does contain some obscene language—so take heed.

An interesting read!

For Question 1 the answer I would choose is D. As is stated, while the fake statistic is ironic, it does speak to our current society and the emphasis we place on numbers. Which reminds me of an example of this emphasis that can be seen in the philosophical school of Positivism, especially in A.J. Ayer's work "Language, Truth, and Logic" where he tries to tear down Metaphysics through the use of a "criterion of verifiability". Ayer even writes that the Metaphysician does not communicate if he cannot verify his claims "empirically".

As for Question 2 the answer I would choose is G, but that is because I do not fully agree with either A or B. Maybe my own answer would be a mixture of both A and B: people seem to use 23andMe out of simple curiosity and desire to know one's self.

I enjoyed this, thank you Dr. Bonanno! Guess I'll finally have to pick up "Lost in the Cosmos".