Many of our linguistic habits are unconscious. We don’t realize we’re saying “like” or “um” until someone points it out or until we watch a video of ourselves. Sometimes, we use words or phrases repetitively or as a verbal filler by default. In my own case, I’ve been guilty of using the words “interesting” and “no doubt” in conversation as unconscious fillers.

With today’s post, I want to reflect a bit on personification and reification, two linguistic phenomena that we engage in all the time without paying attention to them.

These two words seem fancy, but their meaning is quite simple. Obviously, personification refers to the act of personifying. In his Institutes of Oratory, Quintilian treats of personification under the figure of prosopopoeia. Prósopon means “face, person” and poiéin means “to make, to do.” Reification refers to the process of making the abstract concrete. Etymologically speaking, the word “reification” comes from res (meaning “thing”) and facere (meaning “to make”). Otherwise put, reification means thingifying.

Personifying

With personification, we give voice to a person, place, or thing that otherwise wouldn’t have a voice. Quintilian writes:

This figure gives both variety and animation to eloquence, in a wonderful degree. By means of it, we display the thoughts of our opponents, as they themselves would do in a soliloquy, but our inventions of that sort will meet with credit only so far as we represent people saying what it is not unreasonable to suppose that they may have meditated; and so far as we introduce our own conversations with others, or those of others among themselves, with an air of plausibility; and when we invent persuasions, or reproaches, or complaints, or eulogies, or lamentations, and put them into the mouths of characters likely to utter them. In this kind of figure, it is allowable even to bring down the gods from heaven, evoke the dead, and give voices to cities and states.

For Quintilian, then, the figure of personification covers impersonation of persons, places, and things. We need to give voice to others and things as they really might speak. Quintilian continues:

There are some, indeed, who give the name of prosopopoeia only to those figures of speech in which we represent both fictitious beings and speeches. They prefer calling the feigned discourses of men διάλογοι (dialogoi), to which some of the Latins have applied the term sermocinatio. For my own part, I have included both, according to the received practice, under the same designation, for assuredly a speech cannot be conceived without being conceived as the speech of some person.

Thus, Quintilian is admitting that he doesn’t draw a hard line between dialogue, a fictive conversation between persons, and personification proper, or giving voice to non-human artifacts. Any time you imitate a person, living or dead, you engage in personification. All animation is personification (animation, from “anima,” which means soul). Provided this is true, all fiction involves prosopopoeia.

Whenever you make a person speak (or pretend to speak in their voice) when they otherwise wouldn’t, you’re engaging in personification.

Whenever you make a non-living thing speak, you’re also dealing in personification.

We typically think of personification in this latter sense.

In medieval literature, it is not uncommon for Fortune or Philosophy or Death to show up in the flesh. In Chaucer’s “Pardoner’s Tale,” for example, three men set off to kill Death, as if Death were a person.

As sophisticated moderns, we may think we’ve outgrown such symbolic modes of expression. However, whenever someone insists that “Science says” this, that, or the other thing, they’re giving voice to something that literally cannot speak. Strictly speaking, science doesn’t speak. Science doesn’t “say” anything. Scientists do. And sometimes (perhaps oftentimes), they disagree.

Here are some other examples of personification, taken at random:

The phrase “Money talks.” Money doesn’t talk.

Giving the market an “invisible hand.” The market doesn’t have a hand.

The phrase “The evidence speaks for itself.” Evidence doesn’t speak.

Ben Shapiro’s “Facts don’t care about your feelings.” Technically, facts don’t care about anything.

If persons are the most real creatures in existence (as Walter Ong maintains), then personification is an exercise in imbuing something with more existence than it might otherwise have. If we insist that “the research literature says” something, we’re making the literature more real. We’re giving the “research literature” personhood.

Is personification not a bizarre yet commonplace practice in everyday life?

Thingifying

Conversely, reification is a movement of something down the ontological ladder towards something less real. A thing is less real than a person. With reification, we take the voice away of that which could otherwise speak.

If you’ve ever felt like “just a number” when interacting with a gigantic bureaucratic organization, it is because you’ve experienced reification. You’ve been made into a thing (a number). You’ve had your voice taken away.

It is easier to deal with things than with persons. Persons are relatively unpredictable. Why? We can’t say with 100% certitude what will come out of a person’s mouth (even our own). Things are less so. We feel no remorse at manipulating or using a thing. It is just a thing, after all. Reification eases our conscience.

If you’ve ever felt like you’ve been treated as a member of a group instead of a person, you’ve experienced reification. With reification, group identity comes to the fore and obscures individual personhood. As the 20th century attests, reification of entire groups of people into categories and types can be lethal.

Lots of people like to reify themselves as INFJ personality types, in terms of their temperaments (phlegmatic, sanguine, etc.), or even as introverts/extroverts. Of course, you still have a voice if you reify yourself in this manner. But the reification itself serves as a powerful frame for interpreting your own behavior to yourself. Walker Percy liked to poke fun at people who reified themselves in terms of their astrological signs.

Reification serves as a powerful, taken-for-granted frame for self-fulfilling prophecies (i.e., “I acted like that because I’m an introvert, sensitive, etc.” or “He did that because he’s anxious, compulsive, etc.”).

Sometimes, people get reified as “technical” at their respective companies. If you get thingified as a “techie” by your colleagues or supervisor, you may gain certain magic powers (the ability to fix a computer with the wave of a hand) but lose certain rights (the ability to participate in marketing and design discussions, etc.).

In its more perverse forms, reification occurs when we treat particular individuals as members of their groups (group identity triumphs individual identity), when we see individuals simply as manifestations of disease (an instance of COVID-19), or when we treat numbers as more real than that which they refer to (a man with a salary of $150k/yr as more esteemed than his more virtuous blue collar brethren, a student with a 3.2 GPA as more capable of leading others than one with a 2.8 GPA, etc.).

Anytime you thingify yourself or another person, you’re fixing into a static entity something that is dynamic, alive, and ensouled. In the terminology of Martin Buber, you’re making a Thou into an It.

Reification can especially become a problem in the act of interpersonal communication. How often do we communicate with our idea of a given person (an abstraction) as opposed to the person himself? How often do we fix (or reify) our own identities? I am a husband, father, teacher, Catholic, etc. But will I (like Job) lose all those things that make me who I am? If I lose all the things that make me who I am, who would I be?

Reification may be necessary to our knowing anything at all, at least in the empirical sense. I have to fix all of the complex, ongoing transactions that make up economic life into the “economy” if I am to speak intelligibly about inflation. To some degree, I have to fix my identity into “teacher,” “father,” “husband,” etc., so I can behave accordingly in these roles. I have to know you’re a “customer” (and even the “first” in line) so I can issue you your refund. I have to know you identify as a Muslim or a Jew or a Christian or an atheist so I can tailor my speech to your particular identity.

The danger comes with fixing my identity once and for all in any one of these groups. Why? Again, like Job, I can lose everything in this life. If I self-identify with any of these labels too closely, I can experience utter despair when I lose it.

Recognizing What We’ve Made

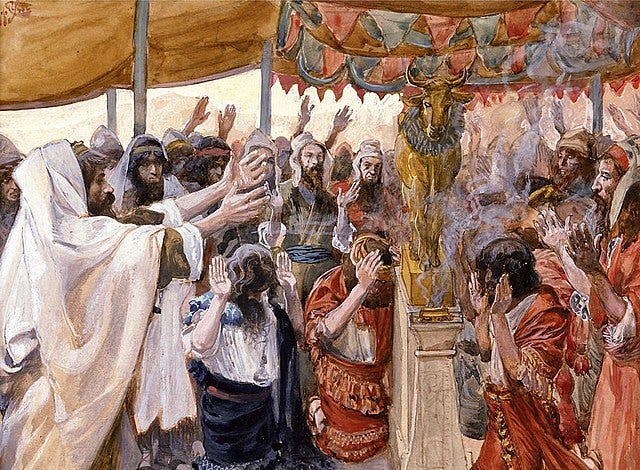

Remarkably, through the Logos and our capacity for speech, we can make persons into things and things into persons. If we unconsciously make things into persons, especially things into God (a Trinity of Persons), we fall into idolatry. Psalm 113 reminds us:

12 The idols of the gentiles are silver and gold, the works of the hands of men.

13 They have mouths and speak not: they have eyes and see not.

14 They have ears and hear not: they have noses and smell not.

15 They have hands and feel not: they have feet and walk not: neither shall they cry out through their throat.

16 Let them that make them become like unto them: and all such as trust in them. (Douay Rheims)

The Psalmist’s expression in the last line is a warning that deifying a mere thing results in a thingifying of oneself. Pushed to the extreme, personification and reification culminate in the destruction of mystery, obscuring the otherness inherent to all personhood, even unto oneself.

What is the antidote to reification in its most pernicious forms? An encounter with reality in its existential plenitude as well as an openness to otherness.

The goal is not to avoid personifying and reifying, per se, but to recognize when and how we do. As Marshall McLuhan might say, there’s no such thing as inevitability when there’s a willingness to pay attention. At least every now and then, we ought to ask ourselves, “Are we aware of the subtle ways that language frames reality for us? Do we recognize how language and other forms of media reify and fix identity? Are we paying attention?”

Thanks for reading. If you liked this post, please press the heart button. A few questions for you to respond to in the comments section:

Who or what would you give voice to?

What would it be fun to personify?

How have you observed reification at play in your life, for better or for worse?

Some notes on sources, more reading, and metacommentary: Technically, you can think of “Science says” as a reification, as a hypostatizing (or making concrete) of a process (i.e., “science” is not a thing but a process or activity of a number of actors working in concert). For the purposes of this article, I wanted to experiment with the idea of the inverse relationship between personifying and thingifying. Alasdair MacIntyre talks about humans as fundamentally unpredictable. Richard Thames is the inspiration for the comments on the phrase “Science says” and evidence not speaking for itself.