How to Wonder: Reading the World like Chesterton

Things need not exist, and yet they do, anyway

I’ve been reading Hugh Kenner’s Paradox in Chesterton. It is one of those books that is out of print but should be in print, even if for the sake of a very limited reading public. Kenner’s short book, published in 1948, runs only 156 pages (which includes footnotes).

This post presupposes at least some familiarity of my audience with Chesterton. If you haven’t read anything by him yet, you can get a nice sampling of his work by checking out the quotations here.

The import of Kenner’s work is manifold. He teaches us to be mindful of how we read Chesterton, and then teaches us how to read the world like Chesterton. At first, Kenner articulates something which I have long felt but been unable to express: Chesterton was a second-rate writer but a first-rate thinker. I know to some Chesterton fans this will sound like blasphemy. But listen. Kenner writes,

Chesterton is not so much great because of his published achievement as great because he is right. His achievement deserves a homage less indiscriminate than it has yet been accorded, and that is part of my business in this book; but I do more than praise what he wrote: I praise what he knew. He cannot be praised too highly so long as praise is confined to what is praiseworthy. His especial gift was his metaphysical intuition of being; his especial triumph was his exploitation of paradox to embody that intuition.

That’s how Kenner’s book opens. It leaves you to question not only how Chesterton thought but how to think like Chesterton. The answer begins in wonder, which is another way of saying that it begins in the things themselves.

Easy to Wonder

The easiest way to begin to wonder is to question why anything should be and to realize that it might not have been. There’s no reason that you should exist. And not only that, there’s no reason for anything around you to exist: this screen, this page, these words, or any word at all. They might not have been. Pick anything in the world around you (including yourself, your child, your spouse, your friend, your notebook, your chair, your little parcel of land, whatever). Now contemplate: It need not have been. You need not have been.

That’s step one: Estrangement from the familiar.

Such a tactic of estranging yourself from the familiar is what I wrote about in my book on Walker Percy. It’s a tactic Percy learned about from the Russian Viktor Shklovsky: defamiliarization. The point of art is to make the stone stony again, to restore the original splendor (and utter strangeness) to the thing. Words, like any other medium, can make things strange for us.

Such, too, is the reason for the religion of art, the elevation of art to the primary portal to re-enter the world. Yet, the glory of art obscures its danger. Chesterton writes,

“When (our contemporary mystics) said that a wooden post was wonderful…they meant that they could make something wonderful out of it by thinking about it.”

Something isn’t truly wonderful because you think so or say so. It’s really wonderful because it’s really wonderful. Chesterton contrasts his own position with that of these so-called mystics:

“I am interested in the post that stands waiting outside my door, to hit me over the head, like a giant’s club in a fairy-tale. All my mental doors open outwards into a world I have not made. My last door of liberty opens upon a world of sun and solid things, of objective adventures. The post in the garden; the thing I could neither create nor expect; strong plain daylight on stiff upstanding wood: it is the Lord’s doing and it is marvellous [sic] in our eyes.”

Chesterton’s point (and Kenner’s) is that things are strange to begin with, even before we start messing around with poetry. “The word is good, but the word can devour the mind,” Kenner writes.

Much of what today consists of postmodern excess lies in this confusion of being and the word, of unduly elevating man’s capacity for speech, as if whatever he says makes it so. As per Kenner, “The post is wonderful because it is there: which is not the same thing as being wonderful because you can read wonders into it.”

The modernist’s excess is to strip language of all its power, to drain it of its blood and leave us with a neutered language of numbers and lifeless syntax. The postmodernist’s excess is to conflate language with being (and Language with Being), leaving us with neither language nor being. Only God can say, “Let there be light” and make light. His Word is truly creative; ours is only partially so.

Even today, especially with our whole cult of authenticity and individual expression, we tend to lose sight of the creative energy reverberating throughout the cosmos independent of our will. Being itself is originally strange, strange in a primordial sense, and it is strange not because we make it strange but because it really is strange. It really is strange because it really is. You either get this basic fact, or you don’t. Kenner explains:

“I believe,” he [Chesterton] wrote, “about the universal cosmos, or for that matter about every weed and pebble in the cosmos, that men will never rightly realize that it is beautiful, until they realize that it is strange…. Poetry is the separation of the soul from some object, whereby we can regard it with wonder.” With the sense of strangeness came the sense of gratitude; not only because, amid so many potentialities, the object at hand might not have been, but also because in its limited being it participated in all Being: in God. He was thankful for a lamp-post because it was not a limpet, but he would have been equally thankful for a limpet.”

In case you’re wondering, a limpet is a type of sea snail.

The easiest way to begin to wonder is to recognize the absolute contingency and absolute necessity of everything. Nothing needs exist, and yet it does, and necessarily so, because God wills it to be. Once you realize that you are not The Maker and that you do not project deeper meanings into the cosmos but that they inhere there from time immemorial, then you can begin exploring the otherwise mundane world right in front of your face.

True wonder at the cosmos is not a projection of the mind but a product of that which is.

Growing in Wonder

So, to reiterate, you can begin to wonder by forcing yourself to see any particular aspect of being as strange (by a sheer act of the will, which, in a real sense is a grace of God). It could be a pencil, a fingernail, your neighbor, eye lashes, beards, etc. Chesterton spent a decent amount of time writing about pocketknives and horses and cheese. His repeated ruminations prove that this exercise can bear repetition. In other words, you can keep doing it, over and over again, as many times as needs be in order to re-enter a world of wonder.

Everything could be otherwise. Giraffes could have small necks. But they don’t. They need not exist, but they do, and not necessarily because you will them to be. They are dependent on something other than you.

Doesn’t their radical independence from you make you feel good? It should be obvious that their independence from you means dependence on something (or Someone) else.

At basic, the world contains many signs of the world to come. Kenner cites Tertullian’s meditation on the repeated death and rebirth of the day as a sign of the resurrection. You can choose to pay attention to these signs, or you can ignore them, if you like. If you take the latter course, however, don’t blame the religious for projecting onto the cosmos that which was happening far before anyone entered the scene. The only true projection is that despair which thinks of the universe as one gigantic cul-de-sac, a dead end. But it is no more a dead end than birth is.

Recently, I’ve been meditating on birth. The reason, of course, is that we have a child on the way, coming very soon. Consider that:

Women have wombs to begin with. This need not have been the case.

Everyone without exception has come from within a womb.

Birth is a death, an entrance that is simultaneously an exit.

Everyone without exception must die.

Death is a birth, an exit that is simultaneously an entrance.

Everyone without exception must take this particular entrance (birth) and must make this particular exit (death).

All of life resembles a womb, especially insofar as our deaths herald a world we have not yet experienced. In this life, we are forever in utero.

We all take the same entrance and the same exit, despite the fact that we are all different. Our sameness is intrinsically tied to our difference (i.e., to express the principle of analogy, we are all the same insofar as we are all different). To go one step further: God Himself dwelt in a womb, and He Himself died. In a strange way, He entered the same womb we’re in. He was born before us insofar as His death preceded ours.

Such paradoxes lie at the heart of existence. We do not read extra, symbolic meaning into the womb. It is there to begin with. The same can be said for this life, all of it, from beginning to end. As the old 90’s lyric has it, “Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end.”

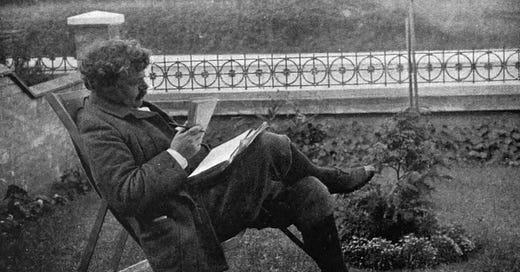

Chesterton made it his life’s work to discover and communicate such paradoxes. Hopefully, you’re interested not simply in reading Kenner’s book but in reading the world around you with new eyes. Kenner writes, “what must be praised in Chesterton is not the writing but the seeing.” Regardless of your talents, perhaps some day someone will issue a similar compliment about you.

Thanks for reading. Hit the heart button if you liked this post. Share it with a friend. If you want to read more about the principle of analogy, check out Gerald Phelan’s St. Thomas and Analogy. As an interesting sidenote, Marshall McLuhan wrote the introduction to Kenner’s Paradox in Chesterton.

What is a screen? Why do they exist the way they do? What would life be like with no screens? A screen, plainly speaking, is an electronic device that displays information in pictorial or textual form. Are they more than that? Of course. After all they are usually connected to the internet. Could the exponential outgrowth of screens be seen as an invasion of our inner most beings fueled by the attention economy? Probably. The Screen always says "look at me. I have something I need to show you." What about the exponential growth patterns of the manufacturing and development of ever increasingly more advanced screens. LOOK AT ME. The demon demands. A full on invasion is occurring and no one is safe.